TOMMY

GUN - Sir

Winston Churchill is seen here trying out an American machine gun for

size.

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill KG OM CH TD DL FRS RA (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, army officer, and writer, who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 and again from 1951 to 1955. Over the course of his career as a Member of Parliament (MP), he represented five constituencies in both England and Scotland. During his time as Prime Minister, Churchill led Britain to an allied victory in the Second World War. He was Conservative Party leader from 1940 to 1955. In 1953, Churchill won the Nobel Prize in Literature for his lifetime body of work; the prize cited "his mastery of historical and biographical description as well as for brilliant oratory in defending exalted

human values".

Churchill was born into an aristocratic family, the grandson of the 7th Duke of Marlborough and son of an English politician and an American socialite. Joining the British Army, he saw action in British India, the Anglo–Sudan War and the Second Boer War, gaining fame as a war correspondent and writing books about his campaigns. Moving into politics before the First World War, he served as President of the Board of Trade, Home Secretary and First Lord of the Admiralty as part of Asquith's Liberal government.

During the war, Churchill departed from government following the disastrous Gallipoli Campaign. He briefly resumed active army service on the Western Front as a battalion commander in the Royal Scots Fusiliers. He returned to government under Lloyd George as Minister of Munitions, Secretary of State for War, Secretary of State for Air, then Secretary of State for the Colonies. After two years out of Parliament, he served as Chancellor of the Exchequer in Baldwin's Conservative government of 1924–1929, controversially returning the pound sterling in 1925 to the

gold standard at its pre-war parity, a move widely seen as creating deflationary pressure on the UK economy.

The Boer Republics declared war on Britain on 11 October 1899 and Churchill travelled to

South Africa to cover the conflict as a war correspondent.

On 15 November, he was on an armoured train in Natal when it was ambushed. He was captured and imprisoned in Pretoria. On 12 December, when the guards' backs were turned, he took his opportunity to escape and clambered over a prison wall into the night. He jumped on a passing train, hiding among sacks, before alighting and enlisting the help of a Transvaal Collieries manager. Churchill arrived in Durban a hero. Back in Britain, stories of his exploits made him famous.

Churchill's new-found fame allowed him to further his political ambitions. At the 1900 General Election he became MP for Oldham.

Churchill delivered his first speech in Parliament in 1901. He had a lisp and overcame this with diligent preparation. After drying up alarmingly in the House of Commons in 1904, he always used detailed notes when he spoke. Churchill was unafraid to disagree with his party chiefs. Together with his friend, Lord Hugh Cecil, he organised a group of young Tory MPs who specialised in harassing their own party leaders – the 'Hughligans'.

From May 1903 Churchill found himself further at odds with much of his own

Conservative Party when he objected to proposed tariff reforms.

Self-confident and supremely assured of his own views, he took a stand against influential politician Joseph Chamberlain. He left the Conservative Party and took a seat on the Liberal benches, flying the flag for free trade. The Conservatives, he said, had abandoned their principles – and he attacked them ferociously. The move paid off. In 1908 he became the youngest cabinet minister since 1866 and the social reforms he pioneered with David Lloyd-George laid the foundations of the welfare state.

Out of office during the 1930s, Churchill took the lead in warning about

Nazi Germany and in campaigning for rearmament.

Hitler invaded Poland on 1 September 1939. By the 3rd, Britain was once again at war with

Germany.

Churchill was immediately recalled from his political exile, again becoming First Lord of the Admiralty. By May 1940, Britain and her allies were losing the war. In the face of the Nazis' relentless march across Europe, Chamberlain bowed to pressure and resigned as

Prime

Minister. When Lord Halifax – the man fancied to assume the Premiership – refused the role, Churchill was the only credible alternative to lead. He also took the post of Minster of Defence and responsibility for the war effort.

STEN

GUN - Sir

Winston Churchill is seen here trying out a British weapon that was

known to jam.

At the outbreak of the

Second World

War, he was again appointed First Lord of the Admiralty. Following Neville Chamberlain's resignation in May 1940, Churchill became prime minister. His speeches and radio broadcasts helped inspire British resistance, especially during the difficult days of 1940–41 when the British Commonwealth and Empire stood almost alone in its active opposition to Adolf Hitler. He led Britain as prime minister until after the German surrender in 1945.

While

the war was going badly and Lord Halifax, the foreign secretary, urged Churchill to negotiate peace terms with Hitler.

The British Expeditionary Force was facing encirclement in France. Churchill, though, was resolute and overruled Halifax. Hundreds of thousands of allied soldiers were evacuated from Dunkirk. France surrendered. On 22 June, French leader Marshal Pétain signed an armistice with Germany. France would be occupied, forced to pay for the German invasion and her army disbanded. Now standing alone, Churchill's speeches stirred Britain to continue fighting until the US and USSR joined the war in 1941.

As the war progressed, Churchill sought to delay the invasion of Nazi-occupied France for as long as possible, fearful of a second

Gallipoli.

But, as pressure from the US and USSR grew, the date was set. On 6 June 1944, US, British and Canadian forces invaded Nazi-occupied France. D-Day had arrived. More than 150,000 troops were landed on French soil in the biggest ever seaborne invasion. At midday, Churchill was able to report the success of the landings to the House of Commons.

On 7 May 1945, Germany surrendered. Though Japan would continue fighting until September, the Allies had won. Churchill had led the nation to victory.

But in the July General Election the Conservatives led by Churchill were roundly defeated by

Labour. Clement Attlee was the new Prime Minister. After two world wars in little more than a generation, Labour policies to raise employment, establish the NHS and nationalise key industries resonated with an electorate voting for change. After his wife commented that the result may be a blessing in disguise, Churchill retorted: "At the moment it seems quite effectively disguised."

After the Conservative Party's defeat in the 1945 general election, he became Leader of the Opposition to the Labour Government. He publicly warned of an "iron curtain" of Soviet influence in Europe and promoted European unity. He was re-elected prime minister in the 1951 election. His second term was preoccupied with foreign affairs, including the Malayan Emergency, Mau Mau Uprising, Korean War and a UK-backed Iranian coup. Domestically his government emphasised house-building. Churchill suffered a serious stroke in 1953 and retired as prime minister in 1955, although he remained an MP until 1964. Upon his death in 1965, he was given a state funeral.

The election of 1945 saw a Labour government voted in and housing policy was central to their welfare reforms in their manifesto. Aneurin Bevan, the Minister of Health, was responsible for the

housing programme which focused heavily on local authority involvement rather than reliance of the private sector. Added pressure on the Government came in the form of soldiers returning from war and rising working class expectations as a result of Labour's promises.

Part of the initial response was programme of short term repairs to existing properties and the rapid construction of ‘prefabs’ – factory built single storey temporary bungalows. These were highly controversial at the time but the Prime Minister of the time, Winston Churchill, was strongly in favour and initiated the Temporary Prefabricated Housing programme. Churchill originally wanted half a million prefabs built across the country as a stopgap measure until labour could be mobilised for more permanent housing. They were expected to last for only 10 years but they proved very popular with some residents. There are still many lived in across the country with 330 in use today in the city of Bristol - one of the largest concentrations of prefabs left in the country. Over the years most prefabs have been demolished and replaced with permanent housing. Modern flatpacks are permanent homes.

The first prefabs were completed June 1945 only weeks after the war had ended. Factories that had previously been employed to build other products such as Aeroplanes were converted to build sections of the innovative new houses. It took a minimum of 40 man-hours to assemble the two bedroom houses complete with plumbing and heating. Sometimes prisoners of war who were still being held in the country were used to help in the construction of the

concrete slabs on which the sections of bungalow were erected. The prefabs could be completed very quickly once the sections were delivered to the site. Unlike traditional houses they had fully fitted kitchens and bathrooms.

On 26 October 1951, little more than four weeks shy of his 77th birthday, Churchill led the Conservatives to electoral victory once again.

Churchill authorised Britain's nuclear weapons programme in 1954 and his final major speech to the House of Commons in 1955 tackled the threat of nuclear destruction.

There was speculation that Churchill may have had Alzheimer's disease in his last years, although others maintain that his reduced mental capacity was simply the cumulative result of the 10 strokes and the increasing deafness he suffered from during the period 1949–1963. In 1963, US President John F. Kennedy, acting under authorisation granted by an Act of Congress, proclaimed him an Honorary Citizen of the United States, but he was unable to attend the White House ceremony.

Despite poor health, Churchill still tried to remain active in public life, and on St George's Day 1964, sent a message of congratulations to the surviving veterans of the 1918 Zeebrugge Raid who were attending a service of commemoration in Deal, Kent, where two casualties of the raid were buried in the Hamilton Road Cemetery. On 15 January 1965, Churchill suffered a severe stroke and died at his London home nine days later, aged 90, on the morning of Sunday, 24 January 1965, 70 years to the day after his own father's death.

Named the Greatest Briton of all time in a 2002 poll, Churchill is among the most influential people in British history, consistently ranking well in opinion polls of prime ministers of the United Kingdom. However, his strongly outspoken views on race and British imperialism have often been criticized. His complex legacy continues to stimulate debate amongst writers and historians.

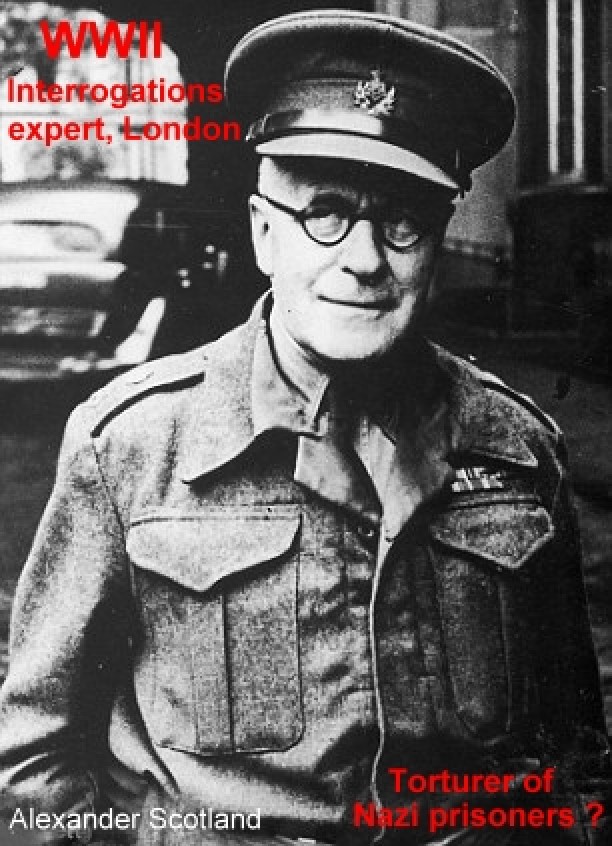

TORTURE -

Although signatory to the Geneva Convention, Nazi prisoners were

tortured. This has not stopped even today where terrorists have been

tortured with the full knowledge of British intelligence who did nothing

to stop those practices. That makes us no better than the Nazi fanatics

that we has set out to potty-train.

WHO

WE WERE FIGHTING AGAINST BETWEEN 1939 AND 1945

|

Adolf

Hitler

German

Chancellor

|

Herman

Goring

Reichsmarschall

|

Heinrich

Himmler

Reichsführer

|

Joseph

Goebbels

Reich

Minister

|

Philipp

Bouhler SS

NSDAP

Aktion T4

|

Dr

Josef Mengele

Physician

Auschwitz

|

|

Martin

Borman

Schutzstaffel

|

Adolph

Eichmann

Holocaust

Architect

|

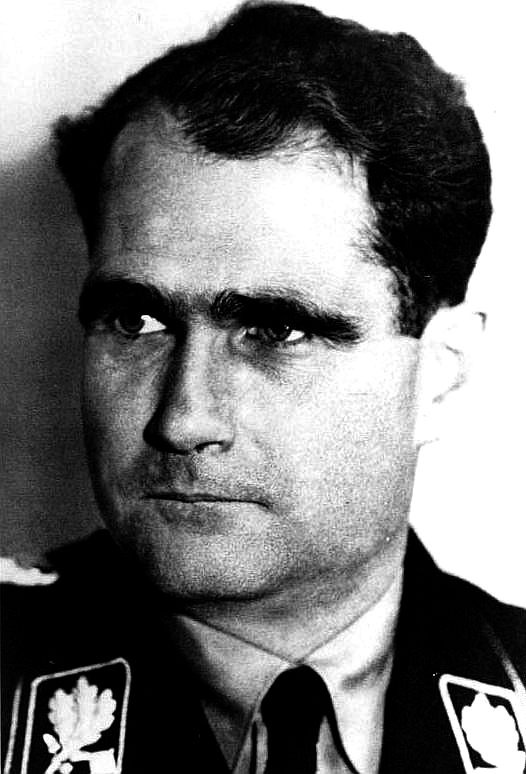

Rudolf

Hess

Commandant

|

Erwin

Rommel

The

Desert Fox

|

Karl

Donitz

Kriegsmarine

|

Albert

Speer

Nazi

Architect

|

CONSERVATIVE

MPS 2017-2018

|

Theresa

May - Prime Mnister

MP

for Maindenhead

|

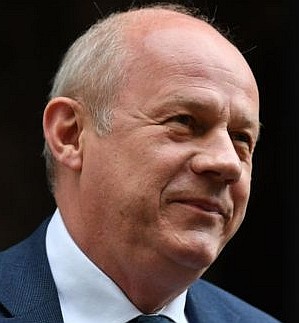

Damian

Green

MP

for Ashford

|

Philip

Hammond

MP

Runnymede & Weybridge

|

Boris

Johnson

MP

Uxbridge & South Ruislip

|

|

Amber

Rudd

MP

Hastings & Rye

|

David

Davis

MP

Haltemprice & Howden

|

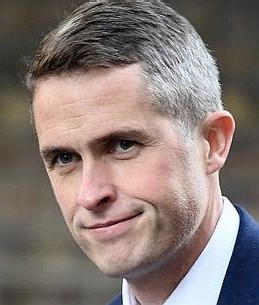

Gavin

Williamson

MP

South Staffordshire

|

Liam

Fox

MP

North Somerset

|

|

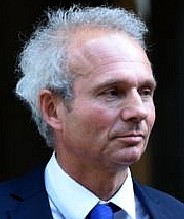

David

Lidlington

MP

for Aylesbury

|

Baroness

Evans

MP

Bowes Park Haringey

|

Jeremy

Hunt

MP

South West Surrey

|

Justine

Greening

MP

for Putney

|

|

Chris

Grayling

MP

Epsom & Ewell

|

Karen

Bradley

MP

Staffordshire Moorlands

|

Michael

Gove

MP

Surrey Heath

|

David

Gauke

MP

South West Hertfordshire

|

|

Sajid

Javid

MP

for Bromsgrove

|

James

Brokenshire

MP

Old Bexley & Sidcup

|

Alun

Cairns

MP

Vale of Glamorgan

|

David

Mundell MP

Dumfriesshire

Clydes & Tweeddale

|

|

Patrick

McLoughlin

MP Derbyshire

Dales

|

Greg

Clark

MP

Tunbridge Wells

|

Penny

Mordaunt

MP Portsmouth

North

|

Andrea

Leadsom

MP South Northamptonshire

|

|

Jeremy

Wright

MP

Kenilworth & Southam

|

Liz

Truss

MP

South West Norfolk

|

Brandon

Lewis

MP

Great Yarmouth

|

MP

Nus

Ghani

MP

Wealden

|

|

Huw

Merriman

MP

Battle

|

Steve

Double

MP

St Austell & Newquay

|

Sarah

Newton

MP

Truro & Falmouth

|

Rebecca

Pow

MP

Taunton Deane

|

|

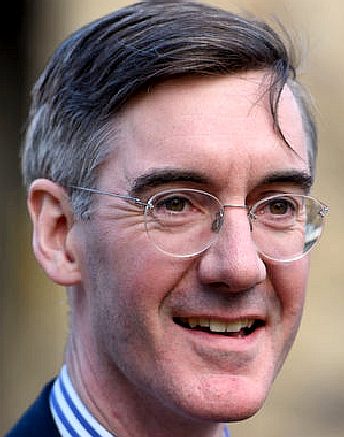

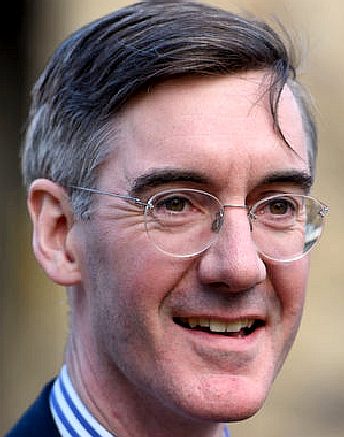

Jacob

Rees-Mogg

MP Somerset

|

Nadine

Dorries

MP

|

Gavin

Williamson

MP

Staffordshire

|

.

.

|

|

.

.

|

.

.

|

David

Cameron

Former

Prime

Minister

|

Margaret

Thatcher

Former

Prime

Minister

|

MP

DAILY

MAIL 26 OCTOBER 2012 -

HOW BRITAIN TORTURED NAZI POWS: The horrifying interrogation methods that belie our proud boast that we fought a clean war

The German SS officer was fighting to save himself from the gallows for a terrible war crime and might say anything to escape the noose. But Fritz Knöchlein was not lying in 1946 when he claimed that, in captivity in London, he had been tortured by British soldiers to force a confession out of him.

Tortured by British soldiers? In captivity? In London? The idea seems incredible.

Britain has a reputation as a nation that prides itself on its love of fair play and respect for the rule of law. We claim the moral high ground when it comes to human rights. We were among the first to sign the 1929 Geneva Convention on the humane treatment of prisoners of war.

[Typically, nations sign, in the hope other

countries abide by the rules, with no intention of playing straight

themselves. It's a bit like tactical voting.]

Surely, you would think, the British avoid torture? But you would be wrong, as my research into what has gone on behind closed doors for decades shows.

It was in 2005 during my work as an investigative reporter that I came across a veiled mention of a World War II detention centre known as the London Cage. It took a number of Freedom Of Information requests to the Foreign Office before government files were reluctantly handed over.

From these, a sinister world unfolded — of a torture centre that the British military operated throughout the Forties, in complete secrecy, in the heart of one of the most exclusive neighbourhoods in the capital.

Thousands of Germans passed through the unit that became known as the London Cage, where they were beaten, deprived of sleep and forced to assume stress positions for days at a time.

Some were told they were to be murdered and their bodies quietly buried. Others were threatened with unnecessary surgery carried out by people with no medical qualifications. Guards boasted that they were ‘the English Gestapo’.

The London Cage was part of a network of nine ‘cages’ around Britain run by the Prisoner of War Interrogation Section (PWIS), which came under the jurisdiction of the Directorate of Military Intelligence.

Three, at Doncaster, Kempton Park and Lingfield, were at hastily converted racecourses. Another was at the ground of Preston North End Football Club. Most were benignly run.

But prisoners thought to possess valuable information were whisked off to a top-secret unit in a row of grandiose Victorian villas in Kensington Palace Gardens, then (as now) one of the smartest locations in London.

Today, the tree-lined street a stone’s throw from Kensington Palace is home to ambassadors and

billionaires, sultans and princes. Houses change hands for £50 million and more.

Yet it was here, seven decades ago, in five interrogation rooms, in cells and in the guardroom in numbers six, seven and eight Kensington Palace Gardens, that nine officers, assisted by a dozen NCOs, used whatever methods they thought necessary to squeeze information from suspects.

Of course, it is crucial to put these events into context. When the gloves first came off at Britain’s interrogation centres — the summer of 1940 — German forces were racing across France and the Low Countries, and Britain was fighting for its very survival. The stakes could not have been higher.

In the following years, large parts of Britain’s cities were left in ruins, hundreds of thousands of service personnel and civilians died, and barely a day passed without evidence emerging of a new Nazi atrocity. Little wonder, perhaps, that it was felt acceptable for German prisoners to suffer in British interrogation centres.

And it should also be said that whatever went on within their walls, it paled into insignificance compared with the horrors the Nazis visited on millions of prisoners.

So, how can we be sure about the methods used at the London Cage? Because the man who ran it admitted as much — and was hushed up for half-a-century by an establishment fearful of the shame his story would bring on a Britain that had been fighting for honesty, decency and the rule of law.

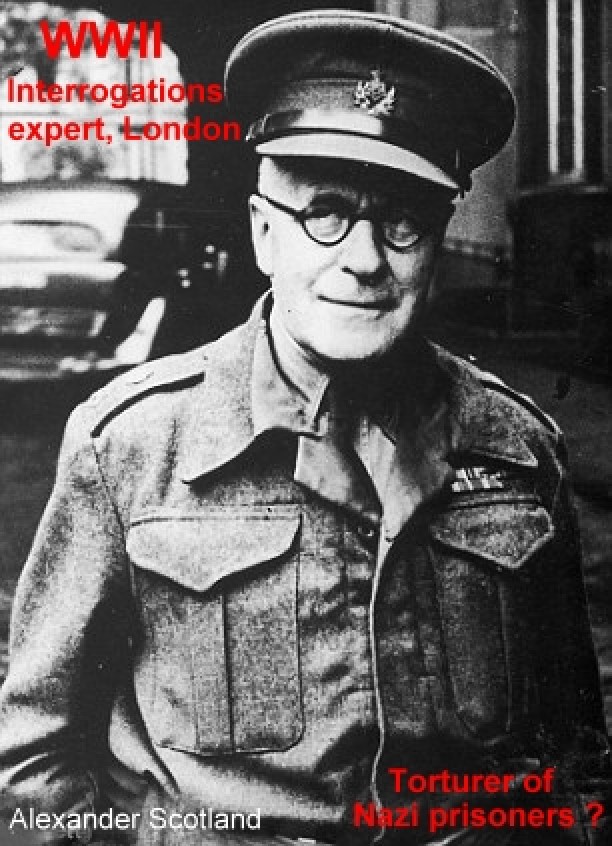

That man was Colonel Alexander Scotland, an accepted master in techniques of interrogation. After the war, he wrote a candid account of his activities in his memoirs, in which he recalled how he would muse, on arriving at the Cage each morning: ‘Abandon all hope ye who enter here.’

Because, he said, before going into detail: ‘If any German had any information we wanted, it was invariably extracted from him in the long run.’

As was customary, before publication Scotland submitted his manuscript to the War Office for clearance in 1954. Pandemonium erupted. All four copies were seized. All those who knew of its contents were silenced with threats of prosecution under the Official Secrets Act.

What caused the greatest consternation was his admission that the horrors had continued after the war, when interrogators switched from extracting military intelligence to securing convictions for war crimes.

Of 3,573 prisoners who passed through Kensington Palace Gardens, more than 1,000 were persuaded to sign a confession or give a witness statement for use in war crimes prosecutions.

Fritz Knöchlein, a former lieutenant colonel in the Waffen SS, was one such case. He was suspected of ordering the machine-gunning of 124 British soldiers who surrendered at Le Paradis in northern France during the Dunkirk evacuation in 1940. His defence was that he was not even there.

At his trial, he claimed he had been tortured in the London Cage after the war. He was deprived of sleep for four days and nights after arriving in October 1946 and forced to walk in a tight circle for four hours while being kicked by a guard at each turn.

He was made to clean stairs and lavatories with a tiny rag, for days at a time, while buckets of water were poured over him. If he dared to rest, he was cudgelled. He was also forced to run in circles in the grounds of the house while carrying heavy logs and barrels. When he complained, the treatment simply got worse.

Nor was he the only one. He said men were repeatedly beaten about the face and had hair ripped from their heads. A fellow inmate begged to be killed because he couldn’t take any more brutality.

All Knöchlein’s accusations were ignored, however. He was found guilty and hanged.

Suspects in another high-profile war crime — the shooting of 50 RAF officers who broke out from a prison camp, Stalag Luft III, in what became known as the Great Escape — also passed through the Cage.

Of the 21 accused, 14 were hanged after a war-crimes trial in Hamburg. Many confessed only after being interrogated by Scotland and his men. In court, they protested that they had been starved, whipped and systematically beaten. Some said they had been menaced with red-hot pokers and ‘threatened with electrical devices’.

Scotland, of course, denied allegations of torture, going into the witness box at one trial after another to say his accusers were lying.

It was all the more surprising, then, that a few years later he was willing to come clean about the techniques he employed at the London Cage.

In his memoirs, he disclosed that a number of men were forced to incriminate themselves. A general was sentenced to death in 1946 after signing a confession at the Cage while, in Scotland’s words, ‘acutely depressed after the various examinations’.

A naval officer was convicted on the basis of a confession that Scotland said he had signed only after being ‘subject to certain degrading duties’.

Scotland also acknowledged that one of the men accused of the ‘Great Escape’ murders went to the gallows even though he had confessed after he had — in Scotland’s own words — been ‘worked on psychologically’. At his trial, the man insisted he had been ‘worked on’ physically as well.

Others did not share Scotland’s eagerness to boast about what had gone on in Kensington Park Gardens. An MI5 legal adviser who read his manuscript concluded that Scotland and fellow interrogators had been guilty of a ‘clear breach’ of the Geneva Convention.

They could have faced war-crimes charges themselves for forcing prisoners to stand to attention for more than 24 hours at a time; forcing them to kneel while they were beaten about the head; threatening to have them shot; threatening one prisoner with an unnecessary appendix operation to be performed on him by another inmate with no medical qualifications.

Appalled by the embarrassment his manuscript would cause if it ever came out, the War Office and the Foreign Office both declared that it would never see the light of day.

Two years later, however, they were forced to strike a deal with him after he threatened to publish his book abroad. He was told he would never be allowed to recover his original manuscript, but agreement was given to a rewritten version in which every line of incriminating material had been expunged.

A heavily censored version of The London Cage duly appeared in the bookshops in 1957.

But officials at the War Office, and their successors at the Ministry of Defence, remained troubled.

Years later, in September 1979, Scotland’s publishers wrote to the Ministry of Defence out of the blue asking for a copy of the original manuscript by the now dead colonel for their archives.

The request triggered fresh panic as civil servants sought reasons to deny the request. But in the end they quietly deposited a copy in what is now the National Archives at Kew, where it went unnoticed — until I found it a quarter of a century later.

Is there more to tell about the London Cage? Almost certainly. Even now, some of the MoD’s files on it remain beyond reach.

Scotland, his interrogators, technicians and typists, and the towering guardsmen left the building in January 1949. The villas were unoccupied for several years.

Eventually, numbers six and seven were leased to the Soviet Union, which was looking for a new embassy building. Today, they house the chancery of the Russian embassy.

Number eight — where it is thought the worst excesses were carried out — remained empty. It was too large to be a family home in the post-war years and in too poor a state of repair to be converted to offices. By 1955, the building had fallen into such disrepair it was sold to a developer, who knocked it down and built a block of three luxury flats. One that went on the market in 2006 was valued at £13.5 million.

The Cage was not, however, Britain’s only secret interrogation centre during and after

World War II. MI5 also operated an interrogation centre, code-named Camp 020, at Latchmere House, a Victorian mansion near Ham Common in South-West London, whose 30 rooms were turned into cells with hidden microphones.

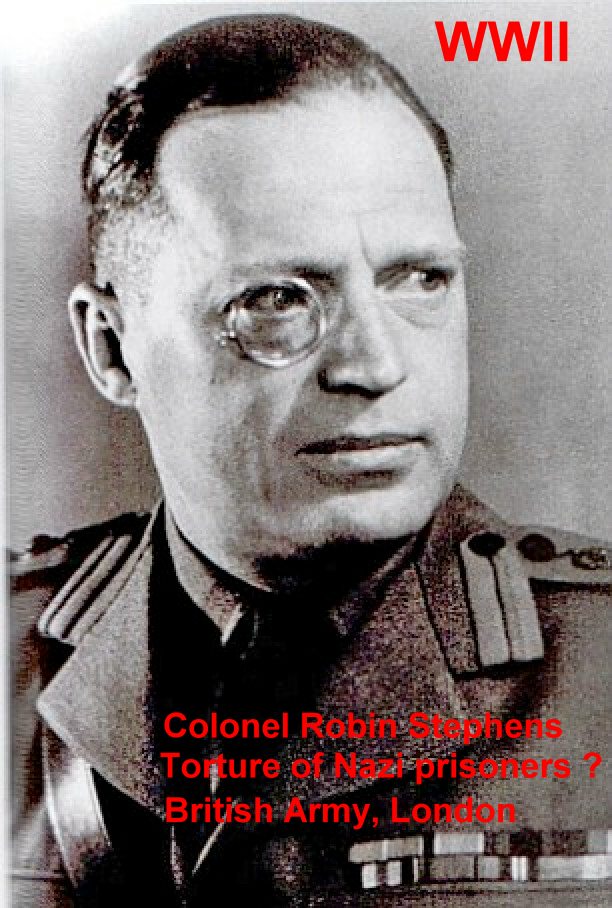

The first of the German spies who arrived in Britain in September 1940 were taken there. Vital information about a coming German invasion was extracted at great speed. This indicates the use of extreme methods, but these were desperate days demanding desperate measures. In charge was Colonel Robin Stephens, known as ‘Tin Eye’, because of the monocle fixed to his right eye.

It was not a term of affection. The object of interrogation, Stephens told his officers, was simple: ‘Truth in the shortest possible time.’ A top secret memo spoke of ‘special methods’, but did not elaborate.

He arranged for an additional 92-cell block to be added to Latchmere House, plus a punishment room — known chillingly as Cell 13 — which was completely bare, with smooth walls and a linoleum floor.

Close to 500 people passed through the gates of Camp 020. Principal among them were German spies, many of whom were ‘turned’ and persuaded — or maybe forced — to work for MI5.

Its first inmates were members of the British Union of Fascists. Some were held in cells brightly lit 24 hours a day, others in cells kept in total darkness.

Several prisoners were subjected to mock executions and were knocked about by the guards. Some were apparently left naked for months at a time.

Camp 020 had a resident medical officer, Harold Dearden, a psychiatrist who dreamed up regimes of starvation and of sleep and sensory deprivation intended to break the will of its inmates. He experimented in techniques of torment that left few marks — methods that could be denied by the torturers and that civil servants and government ministers could disown.

These techniques surfaced again after the war in a British interrogation facility at Bad Nenndorf, a German spa town, in one of the internment camps for those considered a threat to the Allied occupation.

In the four years after the war, 95,000 people were interned in the British zone of Allied-occupied Germany. Some were interrogated by what was now termed the Intelligence Division.

In charge of Bad Nenndorf was ‘Tin Eye’ Stephens, on attachment from MI5, and drawing on his Camp 020 experiences. An inmate recalled him yelling questions at prisoners and then punching them.

Over the next two years, 372 men and 44 women would pass through his hands. One German inmate recalled being told by a British intelligence officer: ‘We are not bound by any rules or regulations. We do not care a damn whether you leave this place on a stretcher or in a hearse.’

He was made to sleep on a wet floor in a temperature of minus 20 degrees for three days. Four of his toes had to be amputated due to frostbite.

A doctor in a nearby hospital complained about the number of detainees brought to him filthy, confused and suffering from multiple injuries and frostbite. Many were painfully emaciated after months of starvation. A number died.

The regime was intended to weaken, humiliate and intimidate prisoners.

With complaints soaring, a British court of inquiry was convened to investigate what had been going at Bad Nenndorf. It concluded that former inmates’ allegations of physical assault were substantially correct. Stephens and four other officers were arrested while Bad Nenndorf was abruptly closed.

But there was a quandary for the Labour government. The political fallout could be deeply damaging. There were other similar interrogation centres in Germany.

From the very top, there were urgent moves to hush things up.

Stephens’ court martial for ill-treatment of prisoners was heard behind closed doors. He did not deny any of the horrors. His defence was that he had no idea the prisoners for whom he was responsible were being beaten, whipped, frozen, deprived of sleep and starved to death.

This was the very defence that had been offered — unsuccessfully — by Nazi

concentration camp commandants at war-crimes trials. But he was acquitted.

The suspicion remains that he got off because, if cruelties did occur at Bad Nenndorf, they had been authorised by government ministers.

Extracted from Cruel Britannia by Ian Cobain, published by Portobello Books at £18.99. © Ian Cobain 2012. To order a copy for £15.99 (p&p free), call 0843 382 0000.

CONSERVATIVE

-

Don't let up lads, really lay into your victims. The public are there

to be drained and beaten to death if they dare to stand in the way of

our agenda to build the greatest empire there ever was. Never mind human

rights and conservation issue, think of all that grey armour and black

leather. The British may not like our uniforms but they like our

methods.

UK

POLITICS

The

United Kingdom has many political parties, some of which are

represented in the House of Commons and the House of Lords.

Below are links to the websites of the political parties that were

represented in the House of Commons after the 2015 General Election:

CONSERVATIVE

PARTY

CO-OPERATIVE

PARTY

DEMOCRAT

UNIONIST PARTY

GREEN

PARTY

LABOUR

PARTY

LIBERAL

DEMOCRATS

PLAID

CYMRU

SCOTTISH

NATIONAL PARTY

SINN

FEIN

SOCIAL

DEMOCRATIC AND LABOUR PARTY

UK

INDEPENDENCE PARTY

ULSTER

UNIONIST PARTY

Conservative

Party

Co-operative

Party

Democratic

Unionist Party

Green

Party

Labour

Party

Liberal

Democrats

Plaid

Cymru

Scottish

National Party

Sinn

Féin

Social

Democratic and Labour Party

UK

Independence Party

Ulster

Unionist Party

We

are concerned with how the make up of the above parties and (reasonably)

popular policies may affect the Wealden district, because we are all

brothers on two islands in the Atlantic

Ocean and what we do or fail to do is likely to rebound on ourselves

and our fellow man in other nations around the world. How we act today

influences policies in other countries in our global community. It is

not just about us and our patch.

DISTRICT

& BOROUGH COUNCILS

East

Sussex has five District and Borough Councils, each with a border on

the coast. From west to east they are:

Eastbourne

Borough Council

Hastings

Borough Council

Lewes

District Council

Rother

District Council

Wealden

District Council

There

is also East

Sussex County Council as the provider of services to the 5 East

Sussex districts.

As

near neighbours and with councils now sharing facilities and working

together, these area of Sussex are included in our remit and an area

where climate

change and affordable

housing are issues that need urgent attention. Where the coastline

is a feature in every Council, Blue

Growth is a food

security issue, especially where this side of of our local economy

is under-exploited.