GAGGING

- You know they are hurting from the truth when they try to gag you.

The state will spout all kinds of spin to make it sound as if they

are accountable and operating transparently. But when it comes to

it, they will seek to prevent publication of any inconvenient truths

such as the Potty

Training episode. Politicians will always do their best to

escape notice and accept the blame when they have done something

wrong. Articles 9 and 10 are supposed to prevent gagging, but do

they work in a United Kingdom that has corruption lurking around

every corner? In terms of freedom ranking, Norway was ranked 1 with

a score of 8, the UK was ranked 39 with a score of 25, where North

Korean was ranked 198th with a score of 98. The North Koreans take criticism

poorly, whereas Norway positively thrive on freedom of the press.

Britain claims to be a free society, but in fact is not up there

with our Scandinavian cousins. Even Costa Rica and Portugal were

markedly freer.

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic media, especially published materials, should be considered a right to be exercised freely. Such freedom implies the absence of interference from an overreaching state; its preservation may be sought through constitutional or other legal protections.

With respect to governmental information, any government may distinguish which materials are public or protected from disclosure to the public. State materials are protected due to either of two reasons: the classification of information as sensitive, classified or secret, or the relevance of the information to protecting the national interest. Many governments are also subject to sunshine laws or freedom of information legislation that are used to define the ambit of national interest.

The United

Nations' 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights states: "Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference, and to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas through any media regardless of frontiers".

This philosophy is usually accompanied by legislation ensuring various degrees of freedom of scientific research (known as scientific freedom), publishing, and press. The depth to which these laws are entrenched in a country's legal system can go as far down as its constitution. The concept of freedom of speech is often covered by the same laws as freedom of the press, thereby giving equal treatment to spoken and published expression. Sweden was the first country in the world to adopt freedom of the press into its constitution with the Freedom of the Press Act of 1766.

RANKINGS

Every year, Reporters Without Borders establish a subjective ranking of countries in terms of their freedom of the press. Press Freedom Index list is based on responses to surveys sent to journalists that are members of partner organizations of the RWB, as well as related specialists such as researchers, jurists, and human rights activists. The survey asks questions about direct attacks on journalists and the media as well as other indirect sources of pressure against the free press, such as non-governmental groups.

In 2016, the countries where press was the most free were Finland,

Netherlands,

Norway,

Denmark and

New

Zealand, followed by Costa Rica, Switzerland,

Sweden,

Ireland and Jamaica. The country with the least degree of press freedom was Eritrea, followed by

North

Korea, Turkmenistan, Syria,

China,

Vietnam and Sudan.

The problem with media in India, the world's largest democracy, is enormous. India doesn't have a model for a democratic press. The Canadian Journalists for Free Expression (CJFE) has published a report on

India stating that Indian journalists are forced—or feel compelled for the sake of job security—to report in ways that reflect the political opinions and corporate interests of shareholders. The report written by Ravi S Jha says "Indian journalism, with its lack of freedom and self-regulation, cannot be trusted now—it is currently known for manipulation and bias."

GREAT BRITAIN

According to the New York Times, "Britain has a long tradition of a free, inquisitive press", but "[un]like the United States, Britain has no constitutional guarantee of press freedom." Freedom of the press was established in Great Britain in 1695, with Alan Rusbridger, former editor of The Guardian, stating: "When people talk about licensing journalists or newspapers the instinct should be to refer them to history. Read about how licensing of the press in Britain was abolished in 1695. Remember how the freedoms won here became a model for much of the rest of the world, and be conscious how the world still watches us to see how we protect those freedoms."

Until 1694, England had an elaborate system of licensing; the most recent was seen in the Licensing of the Press Act 1662. No publication was allowed without the accompaniment of a government-granted license. Fifty years earlier, at a time of civil war, John Milton wrote his pamphlet Areopagitica

(1644). In this work Milton argued forcefully against this form of government censorship and parodied the idea, writing "when as debtors and delinquents may walk abroad without a keeper, but unoffensive books must not stir forth without a visible jailer in their title." Although at the time it did little to halt the practice of licensing, it would be viewed later a significant milestone as one of the most eloquent defenses of press freedom.

Milton's central argument was that the individual is capable of using reason and distinguishing right from wrong, good from bad. In order to be able to exercise this ration right, the individual must have unlimited access to the ideas of his fellow men in “a free and open encounter." From Milton's writings developed the concept of the open marketplace of ideas, the idea that when people argue against each other, the good arguments will prevail. One form of speech that was widely restricted in England was seditious libel, and laws were in place that made criticizing the government a crime.

The King was above public criticism and statements critical of the government were forbidden, according to the English Court of the Star Chamber. Truth was not a defense to seditious libel because the goal was to prevent and punish all condemnation of the government.

Locke contributed to the lapse of the Licensing Act in 1695, whereupon the press needed no license. Still, many libels were tried throughout the 18th century, until "the Society of the Bill of Rights" led by John Horne Tooke and John Wilkes organized a campaign to publish Parliamentary Debates. This culminated in three defeats of the Crown in the 1770 cases of Almon, of Miller and of Woodfall, who all had published one of the Letters of Junius, and the unsuccessful arrest of John Wheble in 1771. Thereafter the Crown was much more careful in the application of libel; for example, in the aftermath of the Peterloo Massacre, Burdett was convicted, whereas by contrast the Junius affair was over a satire and sarcasm about the non-lethal conduct and policies of government.

In Britain's American colonies, the first editors discovered their readers enjoyed it when they criticized the local governor; the governors discovered they could shut down the newspapers. The most dramatic confrontation came in New York in 1734, where the governor brought John Peter Zenger to trial for criminal libel after the publication of satirical attacks. The defense lawyers argued that according to English

common

law, the truth was a valid defense against libel. The jury acquitted Zenger, who became the iconic American hero for freedom of the press. The result was an emerging tension between the media and the government. By the mid-1760s, there were 24 weekly newspapers in the 13 colonies, and the satirical attack on government became common features in American newspapers.

John Stuart Mill in 1869 in his book On Liberty approached the problem of authority versus liberty from the viewpoint of a 19th-century utilitarian: The individual has the right of expressing himself so long as he does not harm other individuals. The good society is one in which the greatest number of persons enjoy the greatest possible amount of happiness. Applying these general principles of liberty to freedom of expression, Mill states that if we silence an opinion, we may silence the truth. The individual freedom of expression is therefore essential to the well-being of society. Mill wrote:

If all mankind minus one, were of one opinion, and one, and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind.

NAZI GERMANY 1933 - 1945

In 1933 freedom of the press was suppressed in Nazi Germany by the Reichstag Fire Decree of President Paul von Hindenburg, just as

Adolf Hitler was coming to power. Hitler largely suppressed freedom of the press through

Joseph Goebbels' Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda.

The Ministry acted as a central control point for all media, issuing orders as to what stories could be run and what stories would be suppressed. Anyone involved in the film industry - from directors to the lowliest assistant - had to sign an oath of loyalty to the Nazi Party, due to opinion-changing power Goebbels perceived movies to have. (Goebbels himself maintained some personal control over every single film made in

Nazi Europe.) Journalists who crossed the Propaganda Ministry were routinely

imprisoned.

RESPONDING TO NEW TECHNOLOGY

Many of the traditional means of delivering information are being slowly superseded by the increasing pace of modern technological advance. Almost every conventional mode of media and information dissemination has a modern counterpart that offers significant potential advantages to journalists seeking to maintain and enhance their freedom of speech. A few simple examples of such phenomena include:

* Satellite television versus terrestrial television: Whilst terrestrial television is relatively easy to manage and manipulate, satellite television is much more difficult to control as journalistic content can easily be broadcast from other jurisdictions beyond the control of individual governments. An example of this in the

Middle East is the satellite broadcaster Al Jazeera. This Arabic-language media channel operates out of

Qatar, whose government is relatively liberal compared to many of its neighboring states. As such, its views and content are often problematic to a number of governments in the region and beyond. However, because of the increased affordability and miniaturisation of satellite technology (e.g. dishes and receivers) it is simply not practicable for most states to control popular access to the channel.

* Internet-based publishing (e.g., blogging, social media) vs. traditional publishing: Traditional magazines and newspapers rely on physical resources (e.g., offices, printing presses) that can easily be targeted and forced to close down. Internet-based publishing systems can be run using ubiquitous and inexpensive equipment and can operate from any global jurisdiction. Nations and organisations are increasingly resorting to legal measures to take control of online publications, using national security, anti-terror measures and copyright laws to issue takedown notices and restrict opposition speech.

* Internet, anonymity software and strong cryptography: In addition to Internet-based publishing the Internet in combination with anonymity software such as Tor and cryptography allows for sources to remain anonymous and sustain confidentiality while delivering information to or securely communicating with journalists anywhere in the world in an instant (e.g. SecureDrop, WikiLeaks)

* Voice over Internet protocol (VOIP) vs. conventional telephony: Although conventional telephony systems are easily tapped and recorded, modern VOIP technology can employ low-cost strong cryptography to evade surveillance. As VOIP and similar technologies become more widespread they are likely to make the effective monitoring of journalists (and their contacts and activities) a very difficult task for governments.

Naturally, governments are responding to the challenges posed by new media technologies by deploying increasingly sophisticated technology of their own (a notable example being China's attempts to impose control through a state-run internet service provider that controls access to the Internet) but it seems that this will become an increasingly difficult task as journalists continue to find new ways to exploit technology and stay one step ahead of the generally slower-moving government institutions that attempt to censor them.

In May 2010, U.S. President Barack Obama signed legislation intended to promote a free press around the world, a bipartisan measure inspired by the murder in Pakistan of Daniel Pearl, the Wall Street Journal reporter, shortly after the September 11 attacks in 2001. The legislation, called the Daniel Pearl Freedom of the Press Act, requires the United States Department of State to expand its scrutiny of news media restrictions and intimidation as part of its annual review of human rights in each country. In 2012 the Obama Administration collected communication records from 20 separate home and office lines for Associated Press reporters over a two-month period, possibly in an effort to curtail government leaks to the press. The surveillance caused widespread condemnation by First Amendment experts and free press advocates, and led 50 major media organizations to sign and send a letter of protest to United States attorney general Eric Holder.

KEY

GLOBAL FINDINGS IN 2017

Global press freedom declined to its lowest point in 13 years in 2016 amid unprecedented threats to journalists and media outlets in major democracies and new moves by authoritarian states to control the media, including beyond their borders.

Only 13 percent of the world’s population enjoys a Free press—that is, a media environment where coverage of political news is robust, the safety of journalists is guaranteed, state intrusion in media affairs is minimal, and the press is not subject to onerous legal or economic pressures.

Forty-five percent of the population lives in countries where the media environment is Not Free. The world’s 10 worst-rated countries and territories were Azerbaijan, Crimea, Cuba, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea,

Iran, North Korea, Syria, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

Politicians in democracies such as Poland and Hungary shaped news coverage by undermining traditional media outlets, exerting their influence over public broadcasters, and raising the profile of friendly private outlets.

United States President Donald Trump disparaged the press, rejecting the news media’s role in holding governments to account for their words and actions.

Officials in more authoritarian settings such as Turkey, Ethiopia, and Venezuela used political or social unrest as a pretext for new crackdowns on independent or opposition-oriented outlets.

Authorities in several countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and Asia extended restrictive laws to online speech, or simply shut down telecommunications services at crucial moments, such as before elections or during protests.

Among the countries that suffered the largest declines were Poland,

Turkey, Burundi,

Hungary, Bolivia, Serbia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

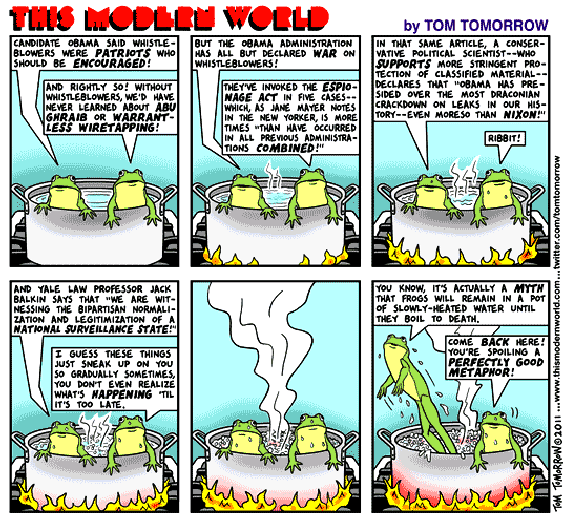

WEALDEN

CLIMATE DIMWITS -

We can only report on what is

happening local to ourselves. You will need to see if your local

authority are acting for the common good, or if they are doing the

same as the climate dimwits in Sussex. This is as of January 2019.

We hope that by the same time in 2020 we can say that our climate

fools have either been on a climate awareness course, or that

planning-speeding has been outlawed in the United Kingdom -

preferably by statute. Because we all know that if there is a

loophole or any gray area at all in the law, this council will use

it to make another fast buck. The old timers at Wealden are like the

frogs

in boiling water. They are so used to creating greenhouse

gases that they actually like it. What about meat free Mondays.

Not in Wealden, it's beef, beef, beef and lamb!

INTERNATIONAL DAY TO END IMPUNITY FOR CRIMES AGAINST JOURNALISTS

The International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists is a

UN-recognized day observed annually on 2 November.

The day draws attention to the low global conviction rate for violent crimes against journalists and media workers, estimated at only one in every ten cases. As these individuals play a critical role in informing and influencing the public about important social issues, impunity for attacks against them has a particularly damaging impact, limiting public awareness and constructive debate.

On 2 November, organizations and individuals worldwide are encouraged to talk about the unresolved cases in their countries, and write to government and intra-governmental officials to demand action and justice. UNESCO organizes an awareness-raising campaign on the findings of the

UNESCO Director-General's biennial Report on the Safety of Journalists and the Danger of Impunity, which catalogues the responses of states to UNESCO’s formal request for updates on progress in cases of killings of journalists and media workers.

UNESCO and civil society groups throughout the world also use 2 November as a launch date for other reports, events and other advocacy initiatives relating to the problem of impunity for crimes against freedom of expression.

BACKGROUND

International Freedom of Expression Exchange (IFEX), a global network of civil society organizations that defend and promote the right to freedom of expression, declared 23 November as the International Day to End Impunity in 2011. The anniversary was chosen to mark the 2009 Ampatuan massacre (also known as the Maguindanao massacre), the single deadliest attack against journalists in recent history, in which 57 individuals were murdered, including 32 journalists and media workers.

In December 2013, after substantial lobbying from IFEX members and other civil society defenders of freedom of expression, the 70th plenary meeting of the UN General Assembly passed resolution 68/163, recognizing 2 November as the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists. The date of the UN day marks the death of Ghislaine Dupont and Claude Verlon, two

French journalists killed while reporting in Mali earlier that year.

IFEX now coordinates the No Impunity Campaign, which advocates year-round for all individuals violently targeted for their free expression.

IFEX

IFEX, formerly International Freedom of Expression Exchange, is a global network of more than 119 independent non-governmental organisations that work at a local, national, regional, or international level to defend and promote freedom of expression as a human right.

IFEX was first proposed in 1992 in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, by a group of 12 non-governmental organisations who met to discuss how they could collaborate on responding to free expression violations around the world. The meeting was organised by the Canadian Committee to Protect Journalists (now Canadian Journalists for Free Expression). Over the next four years, IFEX consolidated its structure, built outreach programs, and established a web presence. By 2007 IFEX had established strategic free expression campaigns and programmes, and as of 2017 IFEX has over 104 network members located in 65 countries worldwide.

Operations

The day-to-day operations of the organisation are run by the IFEX Secretariat based in

Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

IFEX's mandate is to raise awareness by sharing information online and mobilising action on issues such as press freedom, Internet censorship, freedom of information legislation, criminal defamation and insult laws, media concentration and attacks on the free expression rights of all people, including journalists, writers, artists, musicians, filmmakers, academics, scientists, human rights defenders and Internet users.

Campaigns and advocacy

There are a huge number of campaigns happening within IFEX currently. IFEX works with its members by creating and participating in advocacy coalitions and working groups and releasing joint statements and petitions.

In 2011, IFEX launched the International Day to End Impunity campaign. In 2013, the United Nations designated 2 November as the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes Against Journalists. The

Tunisia Monitoring Group (IFEX-TMG), launched in 2004 by 21 IFEX members to raise awareness of censorship and other human rights violations in Tunisia, is IFEX's largest campaign to date. IFEX-TMG was dissolved in January 2013 in response to improved conditions for local NGOs, media independence and free expression rights.

In 2015, Francisco Medina, brother of two journalists murdered in Paraguay in 1997, went before the

United Nations (UN) to speak out against the "deterioration of freedom of expression in his country". The deputy executive director of IFEX, Rachael Kay, also attended in support of Medina.

Online information

IFEX brings attention to free expression stories and events through its website, e-newsletters and special reports. The content is available in multiple languages (English, French, Spanish and Arabic), and addresses pressing free expression stories. The website hosts a searchable online archive of free expression violations going back to 1995.

GLOBAL

WARMING - The Sun

provides us with an infinite supply of energy upon which all life

on earth depends. Our blue

planet has experienced many climate changes in its history, including

the ice age when amazing creatures such a the Dinosaurs

and Mammoths suffered extinction. Man is artificially warming the planet by

burning fossil fuels in some kind of economic arms race that cannot be

sustained and must be brought under control if we are not to extinguish the

lives of many more species such as the Polar

Bears in the Arctic.

News

A to Z directories, please click on the links below to find your

favourite news or to contact the media to tell your story:

There

was a time when you had the time to enjoy the simple pleasures in

life. Now we rarely speak to our partners and have to schedule time

to touch base on the important issues. No wonder the divorce rate is

rising and no wonder our values are changing to reflect the

disposable society we are creating. Instead of helping our

neighbours, some of them we fear, simply because we don't understand

their culture and they ours. Whereas, the world is shrinking due to globalization

and free information exchange, much of which is achieved via the

internet.